I used to take an iris stalk and pretend I was the fairy king. I used to take off my clothes and see how far I could get hiking naked (very far indeed) without being discovered. All the while imagining myself in a far away land, brimming with possibility. I felt ready for college when it approached. I felt ready for anything.

Rude awakening: college was not ready for me.

When I chose my college, I chose the most idyllic but incongruous setting imaginable for a northern kid: Hampden-Sydney College. An all-male perfunctory post-secondary educational institution for decaying southern aristocracy before they became nobody-but-well-paid politicians, mid-level managers at family companies, and leisure-class layabouts. I was not in my element. Nobody wanted a naked, iris-weilding fairy amongst them. But that is a story for another blog post. This post is about using language.

Hampden-Sydney's freshman curriculum did not contain classes in English, Composition, or Public Speaking. Instead, the class was called "Rhetoric." Rhetoric is the art of persuasion — winning people over to your side:

rhetoric (rĕt'ər-ĭk) n. 1.a. The art or study of using language effectively and persuasively. ... 2. Skill in using language effectively or persuasively. —American Heritage Dictionary.The art of persuasion. But it is an interesting choice of title for a class. Anachronistic, almost lurid. Why? Because of this alternative definition:

3.b. Language that is elaborate, pretentious, insincere, or intellectually vacuous.For a college so ready to disown a pupil, this later definition resounds in my head whenever I think about that class. It particularly resounds now that my career is all about "using language persuasively." I often remark that practicing law is the art of getting people to do what they don't want to do. It resounds when I use the word in its primary sense (the use of language), and it reminds me of another story.

One of the tasks with which lawyers are beset is conferring with opposing counsel. Ideally, counsel is dispassionate and polite when speaking to the other side directly. But that is often not the case.

I was in an extended battle with opposing counsel to retrieve certain information during the discovery process. She, as attorneys are wont to do, was hiding something; and I, similarly, was intrigued by the riddle. To keep the information from me, we were arguing about the meaning of a word. I asked her to "look beyond the rhetoric [sense 1.a.]" and realize that her client had the duty to provide the information sought.

That word set her off. "Rhetoric [sense 3.b.]? You think this is about rhetoric?" Indeed, I did, since we were talking about semantics [follow the link, sense 2].

I replied, "Well, its semantics, so yes, we're just arguing about the meaning of this term. I've defined it for you, so please respond according to my definition."

|

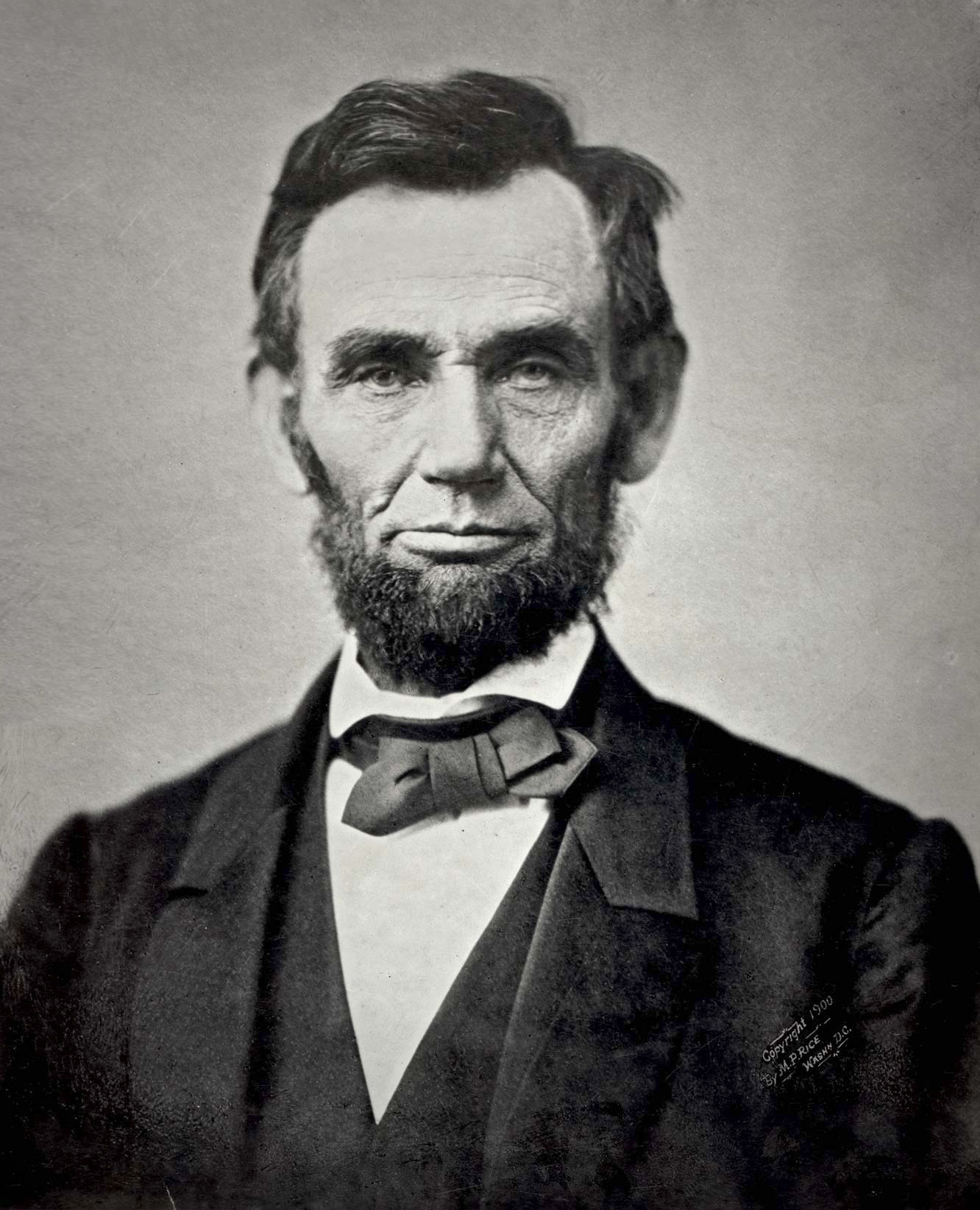

| Image credit: Wikipedia. |

All this is to make my point: Its no wonder that the ancients thought words were magic. Your words often have meaning beyond what you've put behind them. Choose them judiciously and meagerly:

Whatever words we utter should be chosen with care for people will hear them and be influenced by them for good or ill. —Buddha

—Your Bear